A bit about abandoned babies

WHATS IN A NAME?

Giuseppe di Liberato

Giuseppe di LiberatoUnder Napoleon, and continuing even to today although not enforced, it was forbidden to name a male child after his father unless the father was dead. Because of the continued reuse of forenames within a family many Italians, even today are known by their first name followed by their father’s first name.

This meant that in any generation it would be very rare for there to be two people with the same combination of first and father’s names. i.e. Domenico di Antonio.

These names were the administrative names and not always the ones used every day. They are the official names you will see on passports, identity cards, birth certificates, military and notary papers.

By the time the person was ready for marriage you may see his daily name used for the marriage document and almost certainly on the death record.

Since many children were named following the traditional naming practise there might be several children within the same family who bore the same first name, if the previous ones had died.

Female children were often given the feminine version of the male name if the male children did not survive.

Maria, is a name often given to both male and female children. Sometimes every female child will bear the name Maria sometimes in combination with another name sometimes alone. Look carefully at the birth record if the names are separated by a comma, then the names may be used individually but if there is no comma then the name becomes a double-barrelled name. Anna Maria, Maria Rita, Anna Lisa, etc. If there is any kind of verbal abbreviation it will be Maria-ri, or Anna-li, never just Maria or just Anna. In males the double names are often Gian Carlo, Giovan(i)battista or Pietro Paolo, etc.

Domenico/a and Antonio/a are used frequently in the South of Italy. These two Saints were much revered and their names were used in many combinations. In some families you will see each child bearing the name Antonio/a in some combination or other.

A local Saint’s name will be very common in some towns. It may not be the name of the parish. For example, in Rionero Sannitico the parish is San Bartolomeo but the Patron Saint of the town is San Mariano.

Baptism records can be very revealing. A forbidden name such as the father’s name may be added at the time of baptism, thereby flaunting the law. This child may then be known on a daily basis by the diminutive of his father’s name.e.g. The father is Domenico, the child may be Mimmo. Antonio for the father and Tonino for the child. Francesco for the father and Chicco (key-co) for the child.

Of course they still had to use their official name for administrative purposes and on some unofficial records. You may see ˜the namefollowed by the daily name if the father is now deceased. Often you will see that one of the baptismal names is that of the Godparent or the Godparents father, given to honour them but may rarely be used. This is very often the case when one of the local nobility is asked to be the Godparent. In early records where the baptismal indexes are by first name this can be very frustrating as we are often searching for an administrative name that was not the first baptismal name.

Illegitimacy is determined by parentage. Just because you are illegitimate doesn’t mean you were abandoned by your real parents. We all know this, however when researching our Italian ancestors we need to look for the clues that will tell us if they were illegitimate or abandoned since their birth records may not include one or both of their parents names.

Abandoned children were literally abandoned in the local church or left on doorsteps. They may have had some item included in the bundle that would identify them later should either parent want to reclaim the child at a later date. No parent names are included on their birth records. What will be included is a description of where they were found, and the disposition of the child to a local family or a nearby orphanage.

Italy went through a period of extreme poverty during the latter half of the 1800s and many good Catholic families found them selves with more children than they could feed.

This situation affected legally married couples who simply could not bear the expense of yet another child, especially if it was female. Many of these children where in fact abandoned and the family never looked back. In some cases the mother would deliver the child, take it to the ruota, then tell her husband and family the child had died. Others devised a way to keep their child but also benefit from the Government monthly payments to foster mothers. The child would be formally abandoned, the birth registered and the child then ˜fostered back to it’s own parents.

The mother was usually still breast feeding the previous child so could effectively offer a home to the child. She also was paid the monthly fee. This small amount was often just what was needed to help support the entire family. Since these payments continued to age 18 it was a good reason NOT to reclaim your own child just to give it your surname!

At a certain point the number of babies being abandoned by unmarried women was so great and the death rate among these babies so high that the Government also decided to offer a monthly payment to those single women who would keep and raise their child, despite objections that it would increase immorality. This payment also continued until the child was 18 years old.

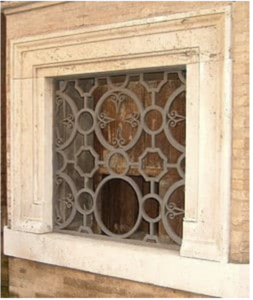

In order to allow the anonymity of the mother, and thus keep her and her family from being disgraced, the ruota dei proietti or “foundling wheel” was instituted. The foundling wheel was a wooden, cylindrical box that was installed in the outer wall of a hospital, church, or in smaller communities, a midwife’s home, into which a newborn could be placed.

The wheel was then turned, so that the baby went inside, without anyone being able to see (from the inside) who placed the baby on the wheel. The person leaving the baby then pulled a bell that was near the wheel, notifying the attendant inside that a foundling had arrived.

These attendants, usually midwives, served as “keepers of the wheel,” and had the responsibility of taking the baby to the town hall to have the birth registered, and then to the parish church for its baptism. They also had the responsibility of finding a wet-nurse to feed the baby. As these wet-nurses were given a small compensation for their services, in some instances the mother of the baby would seek to become the baby’s wet-nurse herself, and have the opportunity of bonding with her baby, even if it was anonymously.

Leave a Reply