PARMA, The Brattisani connections

In the sixteenth century emigration was already widespread in the Parma Apennines: mainly, but not limited to, seasonal migration, directed towards the Maremma Tuscany and Lazio, as it was mainly but not exclusively males who emigrated , but women went too, although fewer in number.

https://www.jenreviews.com/chicken-parmesan-recipe/

Please have a look at this very interesting site with links to fabulous Parmesan recipies.: https://www.jenreviews.com/chicken-parmesan-recipe/

http://www.emigrazioneparmense.it/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=52&Itemid=104

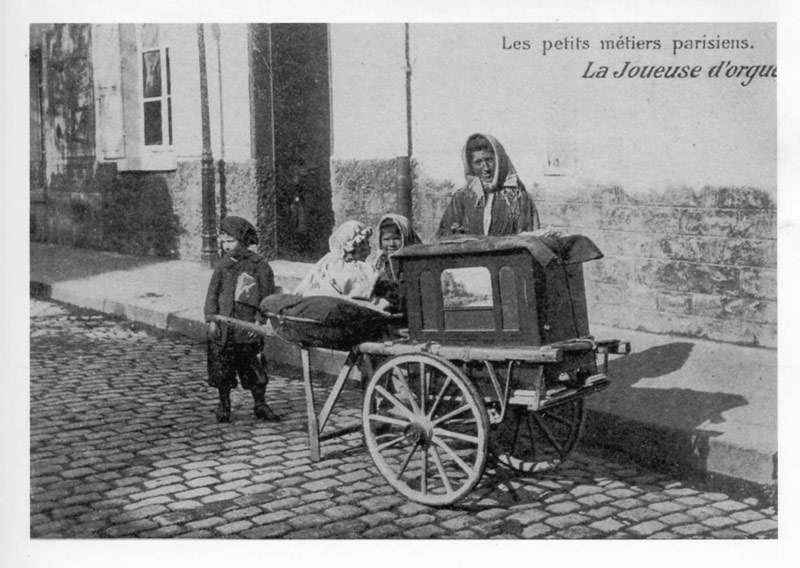

In the eighteenth century, wandering the valleys of the Taro and Ceno knew how to get bears, camels, monkeys and other animals of exotic origin, and these animals, turned Europe, and arrived in Finland, or in Persia, “to procure the food ‘, shows the public and improvised “performances” of the road.

This was one of the most original forms – though not the only one: the others were hawkers of ink or other objects, or the sawyers or daily campaign, when they were forced to take refuge in begging – the relentless struggle waged to overcome the imbalance between the needs of the population and the resources it could draw from the territory.

In both the Napoleonic period in the last decades of the Duchy, the migration is expanding and has often dramatic aspects.

There are serious problems associated with child exploitation and the disintegration of families, the presence of accordion buskers, many of them from Parma Apennines, rise in several countries, including France, England and the United States, bitter controversy and repeated interventions authorities in policing and immigration.

Parma today with her many restaurants.

The city of Parma is located in north central Italy, mid-way between Milan and Bologna. With a population of 170,000, this city is nestled in the fertile valley of the Po River in the heart of the richest of all Italian provinces, the Emilia-Romagna. Although it may not be an indispensable stop on every foreign traveler’s Italian Grand Tour, Parma is a place with a rich history and culture that radiates far beyond the boundaries of its city limits.City of art and music, Parma was home for Antonio Allegri, better known by art lovers as Correggio, and birthplace of Francesco Mazzola, called Parmigianino. Giuseppe Verdi was born a stone’s throw away in Roncole and Arturo Toascanini was a native of Parma. The city’s 12th century Duomo, whose magnificent frescoed dome was painted Correggio, is flanked by a 13th century Gothic bell tower and an exquisite Parma pink marble baptistery. The recently renovated baptistery adorned with statues and reliefs by Benedetto Antelami has been called “the greatest and most original work of the Italian Romanesque.”

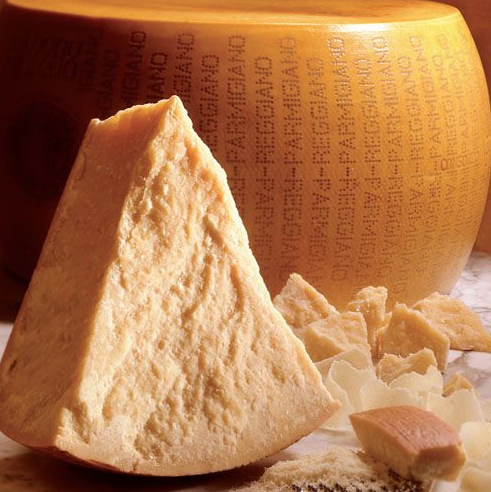

Despite these and other notable claims to fame, the word Parma almost certainly conjures up even more vivid sensations among the gastronomes than among art and music lovers. This is, after all, the capital of Italy’s famous “food valley” where Prosciutto di Parma ham and Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese reign supreme.

What better venue for Italy’s most important food industry trade fair, CIBUS. For one week every two years, Parma’s population nearly doubles with the influx of visitors and exhibitors to this International Food Exhibition.

What better venue for Italy’s most important food industry trade fair, CIBUS. For one week every two years, Parma’s population nearly doubles with the influx of visitors and exhibitors to this International Food Exhibition.

The 1996 record of 120,000 visitors from over 70 countries nibbled their way through a maze of colorful and aromatic stands at the Fiera de Parma fairgrounds located just outside of the city itself.

The pungent aroma of white truffles wafted through the air. At a busy stand representing Italy’s Lazio region, fragrant fleshy black and green olives were on offer at Puglia’s exhibition, as well as tastes of emerald green olive oil on chunks of chewy Italian bread. There seemed to be an inexhaustible supply of pale, paper-thin slices of meltingly tender parma ham at the Consorzio del Prosciutto di Parma stand.

The eighth edition of CIBUS, this year’s fair included some notable innovations, including the inauguration of CIBUS DOLCE, an International Confectionery Exhibition held simultaneously with CIBUS in newly inaugurated pavilion number seven. On display here was a wide range of sweets and desserts from controlled-temperature confectionery and ice creams to cocoa-based and oven-baked products including an endless array of the ever popular biscotti.

from controlled-temperature confectionery and ice creams to cocoa-based and oven-baked products including an endless array of the ever popular biscotti.

This five-day fair, which has grown rapidly since it began in 1985, is a showcase for Italian and Mediterranean food products, a reminder of the wide diversity and quality available here, as well as a place to make a quantity of new discoveries.

This five-day fair, which has grown rapidly since it began in 1985, is a showcase for Italian and Mediterranean food products, a reminder of the wide diversity and quality available here, as well as a place to make a quantity of new discoveries.

And for the truly curious gastronome, a visit to Parma would not be complete without a first-hand glimpse of prosciutto di Parma which we undertook one stormy May afternoon between plenary sessions and Cibus conferences. Our expert guide was Leda Vigliardi Paravia, Italian journalist and food writer. Based in Paris for more than a decade, Leda founded L’Invito, the first Italian cooking school in the French Capital. Happy to be back for a visit to her native country, Leda was an exuberant mentor during our brief stay.

First stop, a small producer of Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese. Behind what seemed like little more than a roadside shop selling one single product, Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese, was an immaculate laboratory production room. In the neighboring ground level “cellar,” hundreds of pale creamy-rind rounds of cheese were stacked on long high shelves like so many dated volumes in a library of precious tomes. And how precious they are!

This is the real McCoy, one of the world’s great cheeses, stamped all around the circumference with the words “Parmigiano-Reggiano” to set it apart from lesser quality cheeses or imitations lumped into the family known to most Americans as Parmesan cheese.

This is the real McCoy, one of the world’s great cheeses, stamped all around the circumference with the words “Parmigiano-Reggiano” to set it apart from lesser quality cheeses or imitations lumped into the family known to most Americans as Parmesan cheese.

Made from the milk of local cows fed on the Po Valley’s green pasture land, Parmigiano-Reggiano is still produced today as it was seven centuries ago. Milk from two different milkings is used. The evening milk rests overnight and is skimmed of its cream before being mixed with the following morning’s new milk.

This mixture is poured into a copper, funnel-shaped boiler and heated gently over an open fire before rennet is added to begin the curdling. The mixture firms and is broken with a giant metal whisk to start the separation of curds from the whey. Next comes the molding, pressing and draining in a form about the size of a large hatbox. After being soaked in a salt brine solution for nearly a month, each cheese is drained a little more before being stacked in cellar to wait patiently for time and nature to transform it into a wonderfully flavorful, grainy-texture cheese.

This mixture is poured into a copper, funnel-shaped boiler and heated gently over an open fire before rennet is added to begin the curdling. The mixture firms and is broken with a giant metal whisk to start the separation of curds from the whey. Next comes the molding, pressing and draining in a form about the size of a large hatbox. After being soaked in a salt brine solution for nearly a month, each cheese is drained a little more before being stacked in cellar to wait patiently for time and nature to transform it into a wonderfully flavorful, grainy-texture cheese.

It is famed for its quality as a grating cheese, particularly for pastas, but is also highly appreciated as a table cheese. At the time of our visit, the going price for this cheese was 32,000 lire per kilo (about $20 for a little over two pounds), which seems expensive until one considers the 500 liters of milk and nearly two years of work required to produce just one Parmigiano-Reggiano. The first taste of an authentic Parmigiano-Reggiano can spoil one forever for the vile imitations often found outside of Italy.

The little pigs of Parma, and its surrounding area, know something about Parmigiano-Reggiano; they grow up drinking the good whey that is drained away from the curds in the cheese-making process. This must contribute to the special flavor of Prosciutto di Parma, better known to many as Parma ham. More important are the special climatic conditions of the breezy hills that surround Langhirano, an area a little south of Parma where nearly half of all the producers of Parma ham are located. We knew that we had arrived in Parma ham country when we begin to see the very long, narrow windows — shuttered or open — designed to ventilate the aging hams.

Prosciutto di Parma production is even more strictly regulated than that of Parmigiano-Reggiano. From the breeding and feeding of the pigs, to the careful selection of legs, the gentle salt rugs and rinsings, and the long hanging and curing in progressively warmer aging rooms, each step in the process must meet certain criteria in order to merit the appellation Prosciutto di Parma. At the end of the 10 to 12 month processing and aging saga, the five-point ducal crown of Parma is branded into each leg that makes the grade, to distinguish it from other cured hams. The result is a raw ham, pale pink in color with a distinctive flavor and a remarkably silky texture.

Prosciutto di Parma production is even more strictly regulated than that of Parmigiano-Reggiano. From the breeding and feeding of the pigs, to the careful selection of legs, the gentle salt rugs and rinsings, and the long hanging and curing in progressively warmer aging rooms, each step in the process must meet certain criteria in order to merit the appellation Prosciutto di Parma. At the end of the 10 to 12 month processing and aging saga, the five-point ducal crown of Parma is branded into each leg that makes the grade, to distinguish it from other cured hams. The result is a raw ham, pale pink in color with a distinctive flavor and a remarkably silky texture.

After two such edifying visits, the only thing we could think of was sitting down to a meal incorporating these two regal products. Our wishes were later fulfilled by the simple elegance of a first course salad composed of peppery rucola greens (better known to some as arugula or rocket) topped with flaky shavings of Parmigiano-Reggiano and paper thin curls of Prosciutto di Parma, all dressed with a drizzle of extra virgin olive oil and lemon juice. We can’t recall what followed, but the memory of that incomparable salad is likely to linger on our taste buds for some time to come.

Leave a Reply